Robert Oliver is a historical novelist whose work examines how risk, power, and decision-making collide under pressure. This month he has published Armada: The Fire, which chronicles the decades leading to the attempted Spanish Armada invasion of England in 1588. Writing for Splash, he argues that there are many lessons commercial shipping can learn from this famous naval skirmish.

In maritime lore, the Spanish Armada is remembered as spectacle: swaggering English hero Francis Drake, towering galleons, running battles in the Channel, and storms that finished what English guns began. It is a story often told as a contest of courage and fate.

But anyone who has spent time in shipping, naval planning, port operations, or maritime risk knows a simpler truth: weather does not cause failure. It exposes it.

The Armada did not collapse because of storms. By the time severe weather intervened in the summer of 1588, the operation was already constrained by decisions made years earlier—decisions embedded in strategy, diplomacy, logistics, and command structure. What unfolded at sea was not a sudden disaster. It was the visible stress failure of a rigid maritime system.

Seen through a modern maritime lens, the Armada was not a battle waiting to be lost. It was a complex, multi-domain operation whose assumptions had hardened long before the fleet sailed. When conditions changed—as they always do at sea—the system could not adapt.

Philip II of Spain governed a global maritime empire built on predictability. Silver fleets from the Indies, convoy schedules, port readiness, and provisioning chains were managed through centralised oversight and strict process. For decades, this system delivered results.

From a shipping perspective, Philip ran an empire optimised for reliability.

The danger emerged when reliability became inflexibility. By the 1580s, Spain faced mounting maritime pressure: persistent English privateering against its trade routes, escalating commitments in the Netherlands, and the need to project force across increasingly contested waters. Each challenge demanded adaptability. Instead, Spain pursued consolidation.

The Armada was conceived as a single, decisive maritime solution—a fleet large enough and orderly enough to impose control, to overthrow Elizabeth, and to make England a Spanish subordinate. But large-scale maritime operations magnify risk when success depends on perfect timing, stable weather windows, uninterrupted supply, and synchronised land-sea command.

Maritime professionals recognise this pattern immediately. Systems designed for control often perform worst under dynamic conditions. When reporting flows upward filtered for reassurance, warning signals arrive late. When authority is centralised, local initiative is suppressed.

Philip’s experience was not insufficient. It was over-leveraged.

England entered the conflict with fewer ships, less capital, and a thinner margin for error. What it possessed instead was operational elasticity.

English naval practice favoured manoeuvrability, decentralised command, and tolerance for disruption. Commanders were expected to adapt to conditions rather than await instruction. English sea power functioned as a pressure system rather than a decisive strike force. This mattered enormously.

Where Spain required smooth coordination between fleet movements, supply schedules, and an army ashore, England exploited asymmetry. Delay became a weapon. Disruption replaced confrontation. The English approach imposed friction on an opponent whose system required flawless execution.

For those in naval affairs or commercial shipping, the contrast is familiar. Smaller fleets survive by shortening decision loops, empowering captains, and accepting uncertainty as a constant. Elizabeth I’s leadership reflected this logic. She preserved flexibility rather than insisting on closure.

The Armada was the endpoint of accumulated decisions, not a singular miscalculation. Diplomatically, pressure replaced negotiation. Strategically, decisive resolution replaced containment. Operationally, complexity replaced resilience.

The plan depended on too many variables behaving predictably: weather, communications, provisioning, vessel condition, and coordination with land forces. Each dependency reduced the system’s ability to absorb disruption.

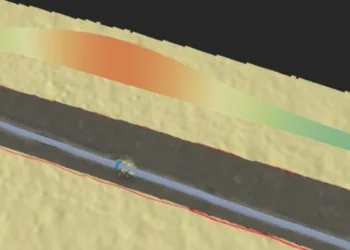

From a modern shipping or naval-planning perspective, the warning signs are obvious. Single points of failure multiplied. Contingency planning narrowed. When conditions degraded incrementally—as they always do—the system unraveled. The sea did not create the failure. It revealed it.

For those working in global shipping, marine insurance, port management, naval operations, or maritime governance, the Armada still matters because it shows how large maritime systems fail.

Institutions become prisoners of their own success. Processes meant to reduce risk suppress uncomfortable information. Flexibility hardens into doctrine. Certainty replaces situational awareness.

The storms that scattered the Spanish Armada were not the cause of failure. They were the moment when a rigid system met an unforgiving reality.

The Spanish Armada reminds us that when power confuses order with control, the sea eventually settles the argument.

For anyone whose livelihood depends on maritime judgment, that lesson has never stopped being relevant.