As someone who’s spent decades immersed in the freight and logistics industry, I’ve learned that freight data often tells the story of the broader economy long before traditional indicators catch up. Right now, that data is painting a stark picture: The U.S. economy is entrenched in a goods recession. While consumer spending on services might be holding steady, the movement of physical goods—the lifeblood of manufacturing, retail, and industrial sectors—has ground to a halt. This isn’t speculation; it’s evident in the high-frequency data we track at FreightWaves through our SONAR platform.

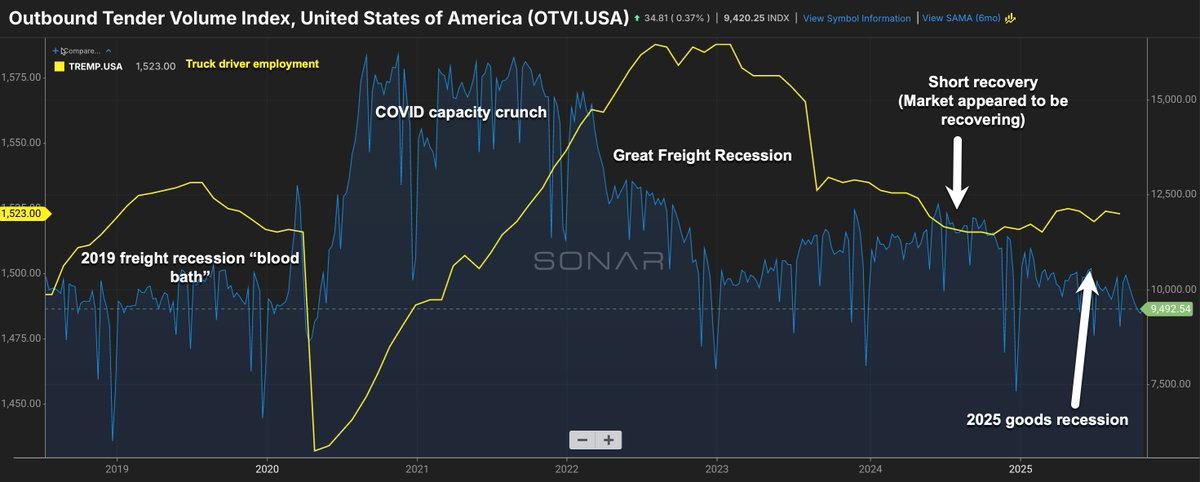

Let me break it down using a key visualization from SONAR that overlays truck driver employment (in yellow) against freight demand, measured by our Outbound Tender Volume Index (OTVI.USA, in blue). This chart spans from 2018 to the present, highlighting the delicate balance—or imbalance—between supply and demand in the trucking sector.

A Turbulent Ride: Freight Markets Since 2018

Starting in 2018, the freight market was already showing signs of strain. By 2019, we entered what we’ve called the “trucking blood bath” recession—a period of overcapacity and plummeting rates that wiped out many smaller carriers. Truck driver employment hovered around 1.5 million, but demand dipped sharply, creating a surplus of trucks chasing too few loads.

Then came 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic. The initial lockdown caused a “capacity crunch” as supply chains froze, but this quickly flipped into a boom. Stimulus checks, e-commerce surges, and inventory restocking drove OTVI to unprecedented highs in 2021-2022. Driver employment spiked to over 1.6 million as carriers scrambled to meet the frenzy. It was a gold rush for trucking, but as we all know, booms don’t last forever.

Enter the “Great Freight Recession” from March 2022 onward. As inflation bit and consumer habits shifted back toward services, freight volumes cratered. OTVI plunged, bottoming out in 2023, while driver employment began a slow but steady decline. Carriers parked trucks, brokers slashed staff, and the industry braced for a prolonged downturn. By the second half of 2024, however, green shoots appeared. I prematurely declared the freight recession over, thinking that capacity had left the industry enough to move the market into balance. OTVI started ticking above truck driver employment, signaling what looked like a recovery. Volumes rose modestly, and spot rates showed signs of stabilization. For a moment, it seemed the worst was behind us.

The 2025 Plunge: Killing the Recovery

But 2025 has delivered a gut punch. As the chart clearly shows, freight demand has nosedived again, dropping to levels not seen since the depths of the pandemic. OTVI currently sits at around 9,420—far below peak levels and down 18% year-over-year. Meanwhile, truck driver employment has reverted to pre-pandemic norms, around 1.523 million, reflecting ongoing capacity adjustments but also highlighting persistent overcapacity.

This sharp volume decline in 2025 isn’t isolated to trucking; it’s a symptom of broader economic malaise in the goods sector.

Manufacturing output has stalled, with PMI readings flirting with contraction. Industrial production is flatlining, and retail inventories are piling up as consumers tighten belts amid high interest rates and lingering inflation.

Of the segments that drive freight, retail is holding up far better than other sectors.

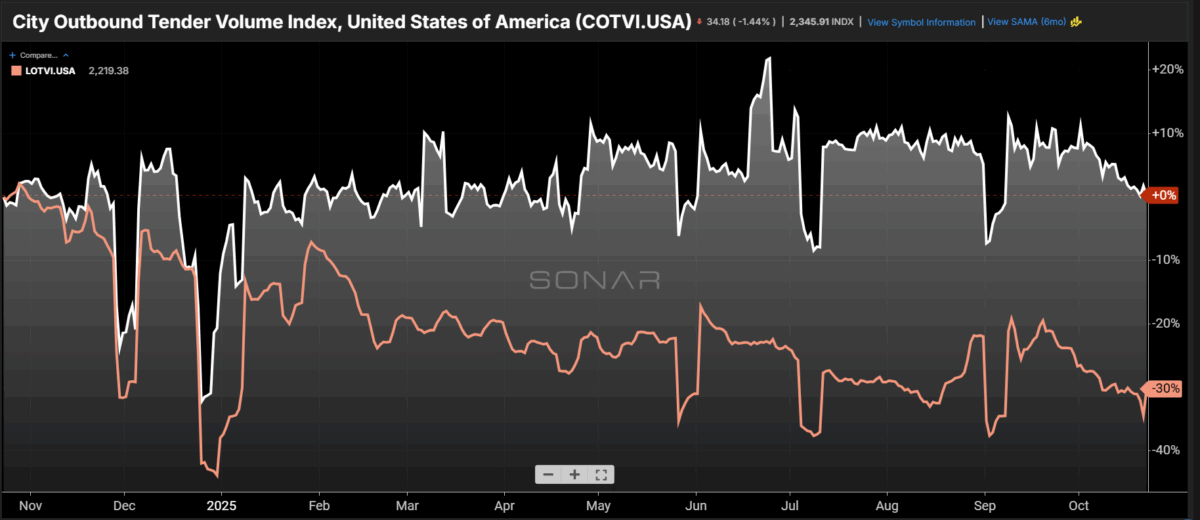

We know this because freight volumes dispatched out of local distribution centers (within 100 miles) are doing okay. Those volumes are flat year-over-year, but not down. The long-haul trucking segment (800+ miles), however, has fallen off a cliff. Year-over-year volumes are down a shocking 30%, a sign that the broader economy is in trouble. Long-haul trucking is more exposed to the energy, manufacturing, auto, and housing segments.

The velocity of money—how quickly dollars circulate through the economy—has slowed dramatically since the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes in 2022, further choking goods movement.

Why does this matter? Freight is a leading indicator. When trucks stop rolling, it’s because factories aren’t producing, warehouses aren’t filling, and shelves aren’t restocking. The data suggests we’re not just in a slowdown; we’re in a full-blown goods recession that could drag on GDP growth if it persists.

Meanwhile, the stock market is making record highs, all driven by speculation tied to the artificial intelligence (AI) boom. When you look at the hyperscalers, they employ just 2 million Americans, while the manufacturing, auto, housing, and transportation segments employ 35 million Americans. Unfortunately for freight markets, the hyperscalers don’t move a lot of freight around, but the 35 million Americans employed in sectors that do are at risk of losing their jobs and their businesses failing. This suggests that the economic pain could compound, especially since the Fed and government seem so out of touch with the realities on the ground.

It certainly feels like a K-shaped economy.

Implications for the Industry

For truckers, a bad economy is not news. After all, the freight market has been in the longest downturn in history: the Great Freight Recession. But a major driver of the freight recession was the overabundance of capacity, caused by a flood of new truck drivers that entered our industry.

The good news is that the administration’s crackdown on unqualified truck drivers—who often have questionable status—should remove a large swath of excess capacity. A blog post that J.B. Hunt posted earlier this week suggested the number could be as high as 600,000 over the next two years, or 17%.

This will provide tremendous relief and usher in the end of the Great Freight Recession, regardless of what happens to the broader economy.

The post Is the goods economy in a recession? Freight data suggests so appeared first on FreightWaves.

(@FreightAlley) November 1, 2025

(@FreightAlley) November 1, 2025