Mike Hosted, the vice president of sales and marketing at trucking-focused financial advisory and accounting firm ATBS, opened up the company’s mid-year webinar Tuesday on the state of the industry by talking about what a lousy trucking market drivers are enduring.

But by the end of his one-hour online presentation, he was showing data how drivers that have stayed with their employer or kept their nose to the grindstone–or in this case, the highway–have actually improved their position in the past few years.

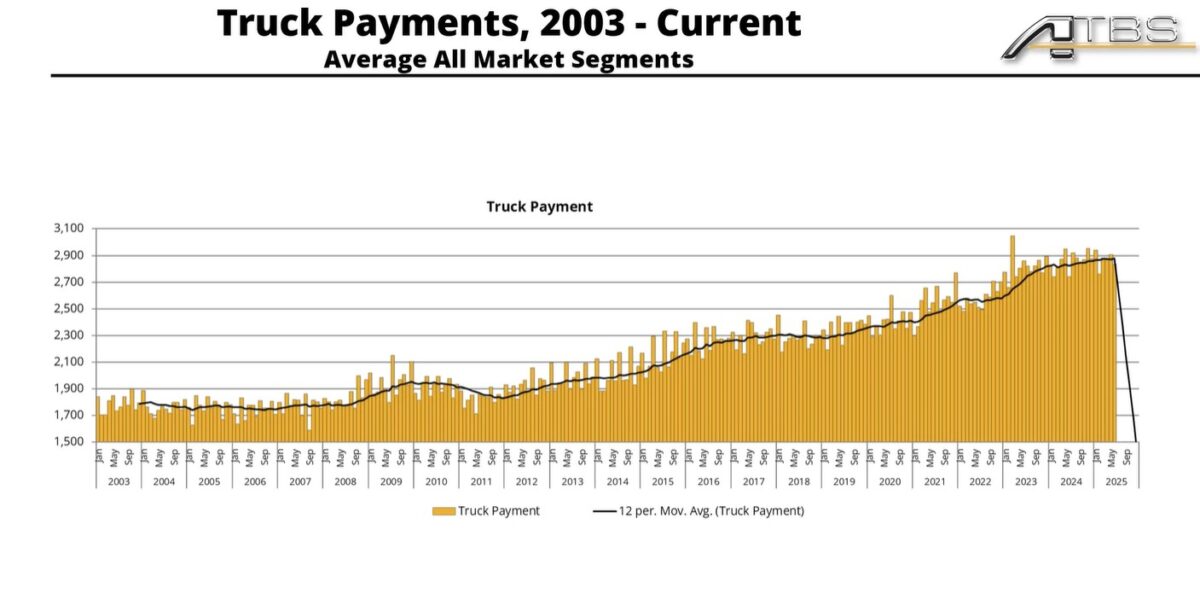

The dichotomy in Hosted’s presentation was stark. He laid out a scenario in which a number of trucking cost centers have been rising, with particularly grim numbers coming out of the bill for maintenance. A chart on truck payments also showed the level of that rising burden.

But Hosted also recommended a series of specific steps that at times morphed into more of a philosophy on how keeping a truck on the road and being willing to steer it into lanes that many drivers might swear off can help spread out higher fixed costs across more miles, leading to better profitability.

Hosted was blunt about the state of the industry that drivers encounter. “Nothing has gotten better with trucking,” he said. “Things haven’t gotten any easier.” His company is in a position to know; it is the financial advisor and tax preparer for an enormous clientele of independent owner operators along with some company drivers.

Staying at your carrier can be profitable

But Hosted, in a series of slides, presented data that showed how drivers that stuck around at carriers for a longer period steadily recorded higher pay. One comparison showed that drivers who stayed with their carrier for more than a year, compared to those who exited quickly, could see about a one-third jump in average income. That gain is created, he said, “by not turning over and not jumping around and doing the right things.”

“I realize that doesn’t work with every carrier,” he said. “I understand the industry but what I can tell you is that there’s a lot of successful carriers.”

Since a bottoming of the industry’s average income levels in the fourth quarter of 2023, per ATBS data, “those drivers that aren’t turning over, that are sticking with it, their net income has gone up every time we’ve done this study for the last two years.”

Incomes coming back from post-crash low

For example, Hosted showed a slide of annualized net income for ATBS clients who have used the company’s services for more than a year. For the top one-third of ATBS clients, annualized net income peaked at $164,929 in the second quarter of 2022. But by the fourth quarter of that same year, it had dipped to $150,006.

That pay level has started to rebound. In the second quarter of this year, that number for the top third of ATBS clients had risen to $161,082.

But to Hosted’s point about being willing to take certain steps, like additional loads or more challenging lanes, there has not been much of a rebound in the bottom third of ATBS clients.

That cohort had average annualized net income or $61,029 in the second quarter of 2022. By the fourth quarter of that year it had dropped to $57,066. But in this year’s second quarter, it had barely moved up, coming in at $57,192.

Most notable were the gains for the top 10% of ATBS clients. Hosted presented data that did not go back as far as the strong market of 2022. But in the second quarter of 2023, their annualized net income was $206,058. In 2025’s second quarter, that figure had risen to $224,715.

All those drivers have faced some increase in costs, as noted by Hosted. But the overall picture for costs in the last year was mostly lower, driven almost exclusively by the decline in fuel prices. (The average weekly retail diesel price published by the Department of Energy/Energy Information Administration was about $3.91/gallon in the first half of 2024. In the first half of this year, it was about $3.59/g.)

What costs are rising are being offset to a large degree by the decline in diesel prices, according to Hosted’s data. The end result is that ATBS’ estimate on trucking variable costs between July 2024 and July 2025 were down 5.6%, to an average annual cost of $65,016. Fuel costs during that time were down more than 10%.

But fixed costs are up 2.1%, or $1,189, to $57,564.

Burden of rising maintenance costs

Hosted’s discussion of maintenance costs was the most pessimistic.

He showed a chart that said in the last year, dry van operators are paying another $1,711 for maintenance, for an annual outlay of $12,483. Reefer maintenance costs have risen even further, to $12,453, up $2,745. The increase in flatbed maintenance has been more moderate, up $486 to $14,087.

“Parts cost more, labor costs more, and people have been running their trucks longer,” Hosted said. Hosted showed data that he said indicated that “we’re skyrocketing to the highest we’ve ever been in terms of monthly maintenance costs.”

That led to a discussion of what Hosted said was likely to be a big factor in the market going forward: deferred maintenance.

When drivers face what Hosted called “tough maintenance or a tough marketplace,” he said drivers will delay maintenance for longer “because they can’t afford to do some of the simple things.”

But delaying maintenance has its limits, he added, “because there’s so many sensors and things that will shut your truck down now, you can’t defer as much as you used to be able to.”

Used truck prices likely to rise

An area of uncertainty Hosted discussed was one where he conceded he believed something different now than he did just a few weeks ago: the cost of used trucks.

The cost of acquiring a truck is likely to be pressured higher, Hosted said. “I thought used truck prices might actually have a chance to go down here in the near future, until this tariff hit,” Hosted said, referring to the recent announcement by the Trump administration to place tariffs on imports of heavy-duty vehicles.

As a result, Hosted said, “we’re going to see fewer orders on new trucks” which as he noted are already at low levels.

“Nobody’s buying new trucks right now because they’re too expensive,” he said. “They’re about to get more expensive.”

Combine that with incomes that by some of the ATBS measurements are higher, but not fantastically higher, and it’s a squeeze. With fewer new vehicles coming in the market, and demand for what is out there on the dealer lots reduced because of economic conditions, older vehicles are going to see their lives extended. “That tells me used truck prices could actually go up when a week ago I might have told you they were actually going to go down,” Hosted said.

But the ATBS webinar was not all doom and gloom on the outlook.

Discussions that Hosted said he has had recently with fleets have led him to optimism on other fronts, but not for the entire sector.

“Some of the smaller fleets right now are struggling,” he said. “They’re struggling with turnover, they’re struggling to find good drivers to stay there.”

That has resulted in what Hosted said was a noticeable drop in service with some smaller fleets. Bigger ones are taking advantage, he said.

“The larger fleets are actually winning back 2% to 3% rate increases, and they’re getting better volume,” Hosted said. In some of the larger fleets–Hosted did not identify them by name but said “you would all know them”–are reporting to ATBS that they’re “getting really good volume back, up 8% to 12% in the freight they’re going to haul over the next year.”

Hosted’s philosophical discussion about how drivers can cope with the current market included some specific guidelines on what a driver should track to mimic those that ATBS are seeing succeed.

Those ATBS clients who are in those categories that have shown income gains despite the weak market, Hosted said, “are taking that extra level. They’re watching their fuel margin. They know their fixed cost per day and they know their variable cost per mile. They’re really just focusing on the numbers.”

But on a broader, less data-driven level, what are the practices that drivers with rising incomes pursue? Holden’s comment: “I can’t say this enough. Extend your range.”

Head to the tough lanes

“I just can’t even imagine what it’s like driving in New York City and the East Coast and all the tolls and things like that,” Hosted said. “But what I’ll tell you is the best paying freight and the best, most profitable drivers go back and forth where people live.”

A recent visit to what he called a “very large carrier” drove home that point, Holden said. A primary route for the company is Chicago to the Northeast; he said the company specialized in that lane “pretty much exclusively.”

“The tolls are high, the fuel costs are high, but the rates they’re getting are the highest,” Hosted said.

Hosted presented a slide that laid out ATBS’ estimates on how a driver would benefit from grabbing more work. The title of the slide: Take an Extra Load.

The numbers laid out were based on ATBS estimates of various costs. Its rate per mile estimate was $1.83; it assumed fixed costs would be zero as other loads would have been adequate to cover them. The variable cost per mile for the purpose of the ATBS example was 70 cents.

And the contribution margin, which Hosted said is one of the most important numbers for a driver to monitor, was estimated at

Hosted said the contribution margin is revenue less variable costs.

Under that scenario, Hosted said, one additional 500-mile load would yield a profit of $565. Doing that monthly would produce $6,780 in profits.

And in the category of obvious, the slide noted that adding two loads per month would double those amounts. .

More articles by John Kingston

ATBS says independent drivers earned a little more in ’24 but drove more as well

As SCOTUS takes up broker liability Monday, new cases arise

California guts key Advanced Clean Fleet Rules; what’s next?

The post ATBS: how a driver can make it in a tough trucking market appeared first on FreightWaves.