Pippa Ganderton, head of ATPI Halo, writes for Splash about the largely unaccounted-for environmental impact of crew change travel and why shipping cannot afford to ignore Scope 3.6 emissions.

Shipping’s efforts to decarbonise are rightly focused on optimising vessel performance, with the aim of reducing fuel consumption and emissions through more efficient propulsion, operational and digital technology, and ship design. These at-source emissions areas are visible, regulated, and increasingly tracked. But alongside the decarbonisation of ships, Scope 3.6 emissions from the global movement of seafarers for crew changes are a significant contributor to the industry’s climate impact.

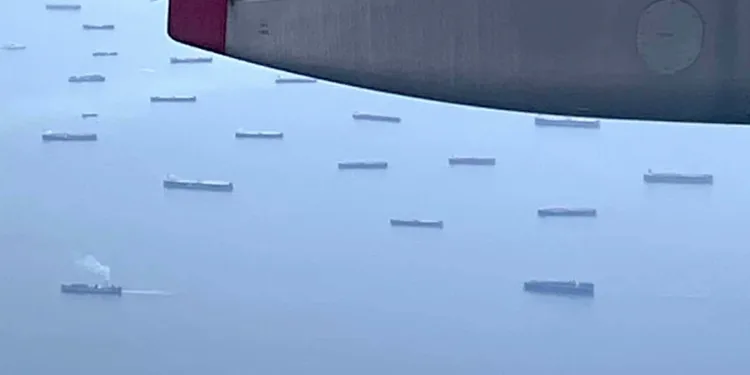

Crew change travel is a critical, operational requirement of global shipping, enabling vessels to operate safely, lawfully, and continuously, and every year, millions of flights are taken to move seafarers between home and vessel. Yet the greenhouse gas emissions from these movements rarely feature in carbon accounting, despite their scale and inevitability.

While Scope 3 emissions are not yet regulated in any national or international decarbonisation framework, many countries are introducing national disclosure regimes that include them. Investor and charterer expectations are also evolving quickly. Maritime operators are increasingly being asked to account for the full extent of their environmental impact, not just emissions generated onboard, but those embedded in their operational ecosystem. In this context, understanding and addressing emissions from crew travel is becoming not only a matter of environmental responsibility, but of commercial credibility.

The first step is measurement. Without quantifying the footprint of crew change travel, it is impossible to establish a meaningful sustainability strategy. Once data is available, operators can begin to identify where, if anywhere, emissions can be reduced. In many cases, opportunities to cut emissions are constrained. Crew change travel logistics are dictated by vessel schedules, port locations, and regional infrastructure. Often, only one or two airline options exist for a given route. Bookings are frequently made at short notice to accommodate operational changes.

Nevertheless, incremental reductions are still possible. When alternative carriers are available, evaluating their fleet efficiency and sustainability credentials can inform decisions. Direct flights, which avoid the carbon intensity of multiple take-offs and landings, are another area of potential improvement (not to mention the potential to keep crew healthier and happier with simpler travel itineraries). These marginal gains may not be transformative, but they contribute to a culture of accountability.

Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is a growing direct reduction mechanism for ship operators, although its current cost and availability remain barriers to widespread adoption. Operators may start with a small SAF investment, for example, covering five or ten percent of travel volumes, and scale over time as budgets and infrastructure allow. This phased approach is often viewed positively by auditors and stakeholders when supported by clear reporting.

Where crew change travel emissions cannot be avoided or reduced, compensation strategies can strengthen a company’s environmental profile or demonstrate to auditors that credible action is being taken to address its footprint.

The effectiveness of such approaches depends entirely on the quality and transparency of the programmes involved. Some specific carbon offset projects have faced legitimate criticism in the past, making third-party certification, robust audit trails and verifiable project documentation essential. While compensation is no substitute for reduction, it offers a responsible and measurable pathway for addressing emissions that remain unavoidable within operational constraints.

In terms of compensation, certain initiatives resonate strongly within the maritime sector. Blue carbon projects, which focus on coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, have particular relevance. The Delta Blue project in Pakistan, the world’s largest mangrove restoration programme, is one such initiative that has seen strong engagement from shipping companies. Its alignment with ocean health, biodiversity and climate resilience makes it a compelling example of sector-specific carbon mitigation. Many organisations combine investments in flagship projects like Delta Blue with other certified forestry or community-based initiatives to balance both environmental and social outcomes.

While Scope 3.6 emissions are not yet a formal reporting requirement across the shipping industry, they are rapidly moving into view. As emissions from vessels are gradually reduced through advances in propulsion and fuels, the proportion of emissions attributable to air travel will become more prominent by comparison. Companies that have already established strategies for measuring, reducing and compensating these emissions will be better placed to respond to both regulatory shifts and stakeholder expectations.