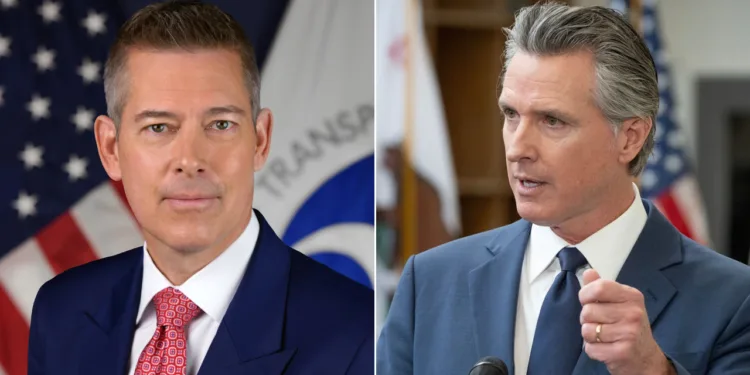

Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy just dropped what I’ve been calling the nuclear option.

In an appearance on Katie Pavlich Tonight Thursday, Duffy made clear that withholding $200 million in federal funding isn’t the end of this fight. If California doesn’t come into compliance on the non-domiciled CDL issue, Duffy said, “we will eventually pull their ability to issue commercial driver’s licenses to anybody in California.”

Not just the 17,000 non-domiciled CDLs at the center of this fight. Every single CDL in the state.

I’ve written extensively about this standoff since the FMCSA released its audit findings last September, which showed that roughly 25% of California’s non-domiciled CDLs were improperly issued. I’ve covered the $160 million funding hit. I’ve warned about the decertification authority in 49 U.S.C. 31312 and 49 CFR 384.405, which most people in this industry didn’t even know existed.

How We Got Here

This didn’t start with the Trump administration’s September 2025 emergency rule restricting non-domiciled CDLs to certain visa categories. That rule, which limited eligibility to H-2A, H-2B, and E-2 visa holders, has been stayed by the D.C. Circuit since November. The court found that petitioners were “likely to succeed” on their claims that the FMCSA violated federal law in its rulemaking.

The California problem predates all of that.

FMCSA’s August 2025 Annual Program Review found California had been violating federal regulations that existed long before Duffy took office. The state was issuing CDLs with expiration dates extending years beyond drivers’ lawful presence documentation. In one case that still makes my blood boil, California issued a driver from Brazil a CDL with passenger and school bus endorsements that remained valid months after his legal presence expired.

That’s not a new rule problem. That’s a California screwed-up problem.

California agreed in November to revoke all 17,000 improperly issued licenses by January 5, 2026. Then, on December 30, the California DMV unilaterally announced a 60-day extension to March 6, citing the need to ensure it doesn’t wrongfully terminate licenses for drivers who actually qualify.

Duffy’s response on X was blunt: “Gavin Newsom is lying.”

FMCSA never agreed to the extension. California proceeded anyway. On January 7, DOT made good on its threat and withheld approximately $160 million in National Highway Performance Program and Surface Transportation Block Grant funds. That’s on top of the $40 million already withheld over California’s refusal to enforce English language proficiency requirements.

The Nuclear Math

California has more than 700,000 CDL holders. The state is home to the nation’s largest trucking workforce, with over 138,000 truck drivers moving freight through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the agricultural heartland of the Central Valley, and every retail distribution center feeding the country’s largest consumer market.

Under full decertification, California would be prohibited from issuing, renewing, transferring, or upgrading any commercial learner’s permits or commercial driver’s licenses until FMCSA determines the state has corrected its deficiencies. Previously issued CDLs would technically remain valid until their stated expiration dates, but here’s where it gets ugly.

Other states could refuse to recognize California credentials during the noncompliance period. FMCSA could issue guidance declaring CDLs issued by a noncompliant state invalid for interstate commerce. The Commercial Driver’s License Information System, which enables interstate verification, could flag every California license.

For the 700,000 CDL holders in the Golden State, decertification wouldn’t just be an administrative headache. It would effectively ground them from operating in interstate commerce.

I’ve been doing compliance work in this industry for over 25 years. I’ve never seen a federal-state confrontation escalate this fast or this far.

What’s That Look Like?

The 17,000 non-domiciled CDLs at the center of this fight represent just over 9% of California’s for-hire carrier base. I believe that number represents just under half the total increase in CDLs

This isn’t really about 17,000 drivers anymore.

J.B. Hunt’s analysis suggests that, between non-domiciled CDL restrictions and English language proficiency enforcement, we could see 214,000 to 437,000 drivers removed from the U.S. supply over the next two to three years. FMCSA estimates that 97% of the current 200,000 non-domiciled CDL holders nationwide won’t be able to satisfy the new requirements under the September rule, assuming it survives legal challenge.

Transport Futures economist Noël Perry puts the at-risk population even higher when accounting for undocumented drivers and new-hire restrictions: potentially 600,000 drivers, or 16% of the active workforce.

Whether those numbers hold up or not, one thing is clear. The days of states running their CDL programs with what Duffy called “reckless disregard” for federal requirements are ending.

What Happens Next

California is stuck between a rock and a hard place it created for itself.

On the one hand, the federal government is withholding $200 million and threatening to revoke the state’s authority to issue any commercial credential. On the other hand, a class-action lawsuit filed by the Asian Law Caucus, the Sikh Coalition, and Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP argues that the DMV’s own administrative errors caused the mismatches in expiration dates and that drivers should be able to immediately reapply for corrected credentials.

The lawsuit names five individual plaintiffs and the Jakara Movement, a Fresno-based organization serving the Punjabi Sikh community. An estimated 150,000 Sikh truck drivers operate in the United States, and many of the affected drivers argue they’re being punished for what amounts to clerical errors by the state.

They’re not wrong about the clerical errors. The DMV admitted in correspondence with federal regulators that “shortcomings of its technical systems and processes” led to the mismatched dates.

That admission doesn’t help California’s legal position with FMCSA. It strengthens it.

If California knew it had systemic programming errors that extended CDL expiration dates beyond work authorization periods, why didn’t it fix them before the feds came knocking? That’s the question that should concern every carrier operating in interstate commerce. A CDL issued in violation of federal requirements may not be valid for interstate operation, meaning drivers holding those credentials could face enforcement action in any state, and carriers dispatching them could face significant liability exposure.

Governor Newsom told the press that DOT had agreed to the March 6 extension. Duffy says that’s not true. FMCSA Administrator Derek Barrs has been equally clear: “We will not accept a corrective plan that knowingly leaves thousands of drivers holding noncompliant licenses behind the wheel of 80,000-pound trucks in open defiance of federal safety regulations.”

California’s argument that its CDL holders are involved in fatal crashes at a rate far below the national average, and that Texas-issued licenses have a 50% higher rate of fatal crashes, might play well in press releases. It doesn’t address the fundamental regulatory compliance issue.

FMCSA didn’t withhold $160 million because of crash rates. It withheld funding because California admitted to issuing 17,000 licenses in violation of federal requirements and then refused to revoke them on the agreed timeline.

The nuclear option remains on the table, and based on everything I’ve seen from Duffy over the past six months, I wouldn’t bet against him using it.

The post California Could Lose Authority to Issue Any CDL Under Duffy’s Nuclear Option. It’s On The Table appeared first on FreightWaves.